My previous post 10 nifty starters for language lessons was popular, with a few thousand views. Since I have been focusing on starters on my site, I thought I’d share another 10 starters I would happily use with classes at various levels. You might find something new here. Or you might not!

1. Guess what I did last weekend

We often ask students what they did last weekend, and I blogged about variations on this theme some time ago here. For this starter, just turn things round and get students to guess what you did. For some languages this is an opportunity for students to use the formal ‘you’ form, which can be tricky to work into lesson plans.

So students make guesses about what you did and you reply yes or no, or give a whole sentence answer - positive or negative - to provide more listening input. As soon as they guess, say, five correct things, the starter is over.

2. Number sequence

One for near beginners who can count to about 50. Read out a sequence of numbers and students must work out the next number in the sequence. For example, 1,2,3,4….. 5. Or 2,4,6,8….10. Or 1,2,4,7,11….16 (adding a rising number if gaps). Another simple one to practise numbers is some basic arithmetic calculations using ‘plus’, ‘minus’ etc). In both cases students can give oral answers or show you on their whiteboards. The latter is better because it ensures every student is taking part.

For more number games, see this post.

3. Vocab recall challenge

Retrieval practice is all the rage (in the UK at least) and for good reason. Cognitive science and common sense tell us that retrieving words or chunks from memory strengthens long-term memory storage. So, give students a category on a slide and get them, individually or in pairs, to recall as many words as possible to a time limit. The time limit encourages fluent, fast recall. Make it competitive by giving a point for every word recalled. You can choose categories to encourage recall of both recently encountered vocab and older words (also a sound cogsci principle). In a recent set of slides I chose categories such as school subjects, verbs, adjectives, animals, places in town, items in your home and sports.

4. Word cloud challenge

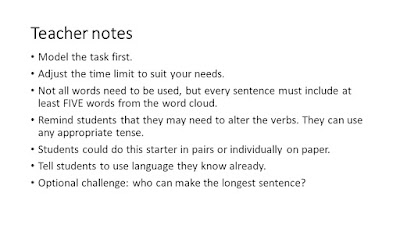

Students make up sentences using words from the cloud. Give a time limit. Below are the instructions, with an example in French. If you prefer something with fewer words, just write up your own instant word cloud on the board, focusing on recent language you have been using in class.

Below are two slides with the teacher notes and word cloud.

5. Tense spotting

7. What happened next?

This draws on students' creativity a bit more, as well as their language skill. Give the class a sentence and ask them, again in pairs of on their own, to write down what happened next. With some classes this could be the basis for some instant story telling or 'story asking' as TPRS teachers call it. This means that you go on to ask more questions and the class continues to build a narrative.

Here are three suggestions for sentences:

I saw my friend carrying a bag in the street.

I heard a strange sound behind me.

I heard the alarm clock and woke up.

8. Find five facts

I blogged about this activity here.

9. Vocab championship

I'm grateful to Florencia Henshaw and Maris Hawkins for reminding me of this format, which they label 'ranking' in their excellent book Common Ground.... (2022)

You know those Facebook play-offs where one item is pitched against another in a vote, then goes to the next round (.g. best band, best drummer) until an overall winner is found? Do the same for areas of vocabulary, such as favourite foods, sports, hobbies, ice creams, school subjects, etc. Display a table like the one below, then elicit votes from the class as you compare two items: Do you prefer vanilla or chocolate ice-cream?

Vanilla

__________

Chocolate

__________ (Winner)

Salted caramel

__________

Pistachio

(Salted caramel is obviously the winner.)

10. Possible or unlikely?

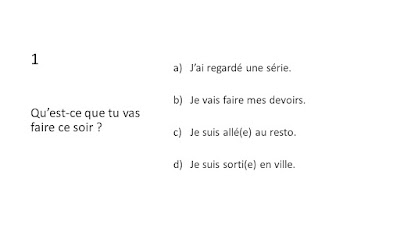

A bit of a staple from language teaching, this one. The focus is on reading comprehension. Just give students a series of sentences and they must judge if the statement is possible or unlikely. Here is an example slide from my collection of 20.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment